RATS! RATS! RATS! YOU’VE GOT A FRIEND IN WILLARD AND BEN

It makes sense that a sequel to the 1971 hit Willard appeared within the next year.

It makes sense that this sequel focused on the rat Ben and would be called Ben, given the previous film’s rather downbeat ending.

It also makes sense that Phil Karlson directed Ben, since Karlson directed such gritty films as Kansas City Confidential, 99 River Street, and The Phenix City Story, all involving characters who might be considered dirty rats.

Karlson never directed any character badder and meaner than Ben, though. Not any of the tough guys played by John Payne, Preston Foster, Neville Brand, Lee Van Cleef, and Jack Elam in Kansas City Confidential. Ben don’t need no stinking mask, for one. Ben also has an infinitely larger gang anyway and they’re real hungry as demonstrated throughout Ben. Nor Tennessee sheriff Buford Pusser from Walking Tall, which Karlson made right after Ben. Joe Don Baker must have come as quite a relief after Ben, who quickly became a has been after his two film roles and multiple songs about him. Ben must have wanted even more dough to return for a third film. That dirty rat!

Ben also won a PATSY Award for his performance in Ben, which undoubtedly contributed to his ego problem.

Anyway, I didn’t much care for Ben, because it quickly established a dread pattern after the obligatory flashback to the events that ended Willard. Here’s that pattern: Rat attack. Cutesy poo musical number. Rat attack. Cutesy poo musical number. Rat attack. Cutesy poo musical number. Rat attack. Cutesy poo musical number. Rat attack. Cutesy poo musical number.

Sounds like a real winner, right? Yeah, if you like a bunch of bad ideas bouncing off each other for 90 minutes.

You can also throw in some police chatter, a journalist character who’s seemingly working on just this one story (though it’s hard to blame him, I mean it’s not everyday that millions of street rats terrorize a city), and a little boy named Danny and his sister (played by Meredith Baxter before her marriage and hyphenated name, before her TV mother fame, before her Lifetime movie career, before her coming out) and his mother who all seem like refugees from a Disney live-action project.

Oh yeah, like Willard before him, the little boy possesses the ability to communicate with rats, especially Ben. Oh yeah, once again, the lonely little boy has a heart condition.

Danny proves responsible for the musical numbers scattered throughout Ben and he even gives Ben a puppet show. Wow, just wow.

A 13-year-old Michael Jackson sings “Ben’s Song” over the end credits and “Ben” competed against songs from The Poseidon Adventure, The Little Ark, The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean, and The Stepmother for Best Original Song at the 1973 Academy Awards. “Ben” lost to “The Morning After” from The Poseidon Adventure, believe it or not, and having heard both songs, I don’t believe it since “The Morning After” defines godawful. Unfortunately so does most of the movie Ben.

I’ll give Karlson and animal trainer Moe Di Sesso their due for amplifying the rat count to 4,000 for Ben. Eight times the rats as Willard, but that’s the only area in which Ben triumphs over its older brother. Granted, one human year translates to approximately 30 in rat years, so maybe that’s why Ben’s motion picture career stopped after two films in two years.

Rating: One star.

— What else can I say other than I liked Willard and I would not be surprised if I found out that it played as one-half of a double bill with fellow 1971 cult film Harold and Maude.

Both are weird little items with a delightfully morbid sense of humor and I only say delightfully because I like both films, and they have offbeat lead characters who push the patience of every adult.

Bruce Davison stars as Willard Stiles, who must contend with a harridan mother (Elsa Lanchester) and a bully for a boss (Ernest Borgnine). Willard develops a close relationship with Ben and Socrates, who unfortunately for Willard are rats. See, Willard finds out that he can communicate directly with rats and that he enjoys their company more than his fellow human beings, especially his overbearing mother and all her overbearing friends and his asshole boss. His mother wants Willard to get rid of them damn rats and his boss, well, he develops genuine distaste for Rattus norvegicus after Willard’s rats crash his party one night.

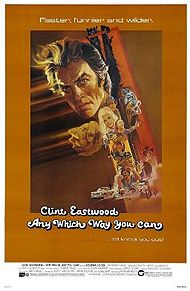

Willard also begins a tentative, very tentative relationship with his lovely temporary co-worker Joan (Sondra Locke). In the end, Willard should have pursued Joan more than Socrates and Ben. No doubt that our lad Willard would have lived a whole lot longer.

As interesting as it was to watch Davison and Locke early in their careers and Lanchester (The Bride from The Bride of Frankenstein) late in her career, Borgnine proved to be the key component in the success of Willard. For a picture like Willard to work any whatsoever, we need a character that we love to hate and Borgnine’s Al Martin suitably fills that need. For us to fully anticipate and then relish his inevitable death, Borgnine needed to work us into a frenzy every time he’s onscreen. Borgnine does that and then some, especially when he seizes upon Socrates and kills him with delight. We know then, more than ever before, that Martin will meet a spectacular demise.

Borgnine won the Academy Award for Best Actor in 1956 for his extremely likable performance as the title character in Marty, directed by Delbert Mann. Sixteen years later, in a picture directed by Daniel Mann, Borghine mined the opposite end of the character spectrum for Martin.

For sure, Borghine might be the first, last, and thus far only Academy Award-winning actor to be annihilated by rats.

That alone is worth the price of admission.

Rating: Three stars.