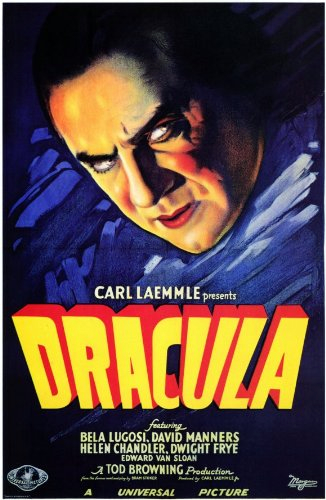

DRACULA (1931) ****

I remember being first disappointed by the 1931 Dracula and that disappointment carried over for more than two decades.

Around the turn of the 21st Century, I bought the 1999 VHS release and that’s what I first watched, the one with Classic Monster Collection across the top and then New Music by Philip Glass and Performed by Kronos Quartet immediately below. Of course, I thought Bela Lugosi as Dracula and Dwight Frye as Renfield were absolutely incredible, David Manners as Jonathan Harker and Edward Van Sloan as Professor Van Helsing and Helen Chandler as Mina Harker less so, and I loved director Tod Browning’s 1932 Freaks at first sight contemporaneous with Dracula. Freaks remains one of my absolute favorite movies, so obviously some movies hit people right from the start and others just simply take more time or sometimes they never make that deep, personal connection others do.

For the longest time, at least a decade if not longer, I thought Dracula was overrated and paled in comparison against Freaks, Frankenstein, The Bride of Frankenstein, and The Wolf Man, all of which I first saw around the same time as Dracula and I loved, absolutely loved, and still do love all of them. At the time, I also loved Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein more than Dracula.

It was that darn Philip Glass / Kronos Quartet score that stank up Dracula and I still get a big kick out of the Triumph the Insult Comic Dog couplet, Philip Glass, atonal ass, you’re not immune / Write a song with a fucking tune. I remember my wife complained about Glass’ score for the experimental non-narrative film Koyaanisqatsi and I bristled at his score for Candyman upon revisiting that 1992 film for the first time in several years.

Revisiting the 1931 Dracula in recent years, without the Glass / Kronos score and back closer to how it first appeared in theaters on Feb. 14, 1931, it’s risen in stock from three to three-and-a-half and finally four stars. I cannot deny that it still has a fair share of faults, like those performances I mentioned earlier and the stage-bound production quality since it’s based off the 1924 stage play adapted from Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel, but I’ve grown appreciation for everything that works from the opening scenes in Transylvania to Lugosi (1882-1956) and Frye (1899-1943), who inspired later songs from Bauhaus (Bela Lugosi’s Dead) and Alice Cooper (The Ballad of Dwight Fry).

It also helps one to catch up with the Spanish language Dracula from the same year and the same sets but a different cast, a different language, and a different director. This Spanish version, rediscovered first in 1978 and then later on video in 1992, lasts 30 minutes longer and it’s better in almost every respect than its famous counterpart. Better shot and better looking, vastly superior cleavage and far sexier women (Lupita Tovar over Helen Chandler any day of the millennium), and less wimpy men in the Spanish version, but Lugosi still prevails against Carlos Villarias.

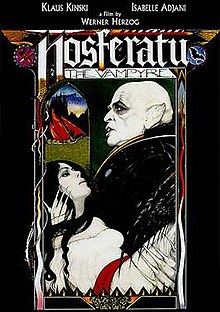

Several lines had already entered the lexicon decades before I first watched Dracula: I never drink … wine. For one who has not lived even a single lifetime, you’re a wise man, Van Helsing. Listen to them. Children of the night. What music they make. Even I am Dracula belongs somewhere in the pantheon near Bond, James Bond. Lugosi’s ability or lack thereof speaking the English language actually benefits the otherworldly nature of his Dracula and I hold his performance in high regard alongside Max Schreck in Nosferatu, Christopher Lee in Dracula, and Gary Oldman in Dracula.

I have a long relationship with vampires.

I remember the 1985 Fright Night being the highlight of a boy slumber party circa 1988 and third or fourth grade.

I must have been 11 or 12 years old and in the fifth or sixth grade when reading the Stoker novel. Right around that point in time, I also read Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Hound of the Baskervilles and Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. I loved all three of them and they each fired up my imagination and creative spirit.

A few years later, I caught up with the Francis Ford Coppola version and talk about a movie that wowed a 14-year-old boy. I remember staying up late and sneaking around (somewhat) to watch this Dracula on my bedroom TV, captivated by all the nudity and sexuality and violence and Winona Ryder and Sadie Frost and it recalled some of what I liked about the novel all while becoming a cinematic extravaganza. I know critics of the 1992 Dracula blasted the film for being all style, no substance and for being overblown, but I think it’s overflowing with creativity and sheer cinematic beauty. I rate it right up there with F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu as one of the best vampire films ever.

Some things simply transcend Keanu Reeves’ horrible accent and Dracula’s at one point beehive hairdo.

The vampire genre itself transcends such duds as Dracula 2000 and New Moon.