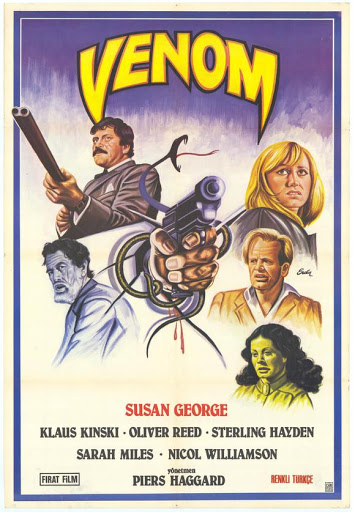

VENOM (1981) ***

I just finished considering Silent Rage, a film that runs Chuck Norris, a Western, Animal House, mad scientists, and a madman killer made indestructible through a cinematic blender.

Thus, I feel safe in saying that Silent Rage prepared me for Venom, a British horror film that has a distinguished multinational cast, kidnapping and hostage negotiation, and only the world’s deadliest snake, the dreaded Black mamba from sub-Saharan Africa. The mamba gets a few closeups, more than Norma Desmond in Sunset Boulevard and Daffy Duck in Duck Amuck, and its own POV. Yeah, we’ll call it the Black Mamba Cam.

That distinguished cast includes kidnappers Klaus Kinski and Oliver Reed, Scotland Yard commander and lead negotiator Nicol Williamson, snake expert Sarah Miles, slinky (won’t call her slutty or a snake expert in her own right) nurse Susan George, and lovable crusty old grandfather Sterling Hayden.

Basically, Venom contains three movies within one — the kidnapping inside the house, the hostage negotiation and the behind-the-scenes police maneuvering on the outside, and the deadly snake on the loose. We’ve all seen kidnapping and hostage negotiation plenty before, on TV cop shows and in the movies, but very rarely do the kidnappers have to deal with the world’s deadliest snake. And Lord knows we’ve all seen a bad snake movie or two, like for example the 1972 disaster Stanley, which populated its killer snake scenario with thoroughly unpleasant and despicable characters, a somewhat heavy-handed environmental message, and some of the dopiest music ever heard by man this side of Jonathan Livingston Seagull.

Venom turned out to be a far more enjoyable motion picture experience than Stanley. For example, the scene in Venom where the boy picks up the mamba by mistake and unknowingly transports the world’s deadliest snake from one side of London to another brought to mind the classic sequence in Sabotage that ends in the death of a young boy named Stevie. The inevitable scenes late in the picture when the mamba strikes Reed and Kinski are both well worth their wait, and the mamba’s strike at George about 30 minutes into the picture lets us know that we’re in for a treat when Reed and Kinski do meet their demise.

Later that day, much later in the day to be precise, though, I watched Murders in the Zoo from 1933 and imagine my delightful little surprise when a mamba figured prominently in that older film’s plot. The gruesome hits in Murders in the Zoo just keep on coming down the home stretch, especially when a boa constrictor consumes the dastardly big-game hunter, bastardly zoologist, and insanely jealous husband played by Lionel Atwill.

Venom and Murders in the Zoo both find perfect ways to deal with snakes in the grass.