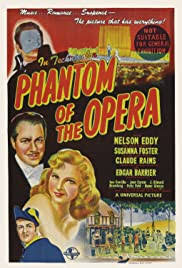

PHANTOM OF THE OPERA (1943) **

I put off watching a sound version of Phantom of the Opera for the longest time and the 1943 Phantom of the Opera only confirmed that suspicion and doubt.

Claude Rains did not even remotely approach what Lon Chaney accomplished in the 1925 silent version and I have to face the fact that I am definitely not the world’s biggest opera fan.

Yes, I do realize that I made it through A Night at the Opera and Opera with relative ease, but predominantly because I am big fans of both the Marx Brothers and Dario Argento, not opera.

Allan Jones’ production numbers in both A Night at the Opera and A Day at the Races, as well as James Whale’s Show Boat, are why they invented the fast-forward and skip buttons. The Marx Brothers’ numbers are infinitely better on the ears.

As for Argento, he goes so far over the top (especially in the murder sequences) that I find his operatic excess in Opera enjoyable.

Universal Studios invested $1.75 million on Phantom of the Opera (both Phantom and fellow 1943 release Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man received much larger production budgets than previous Universal releases, like, for example, the $180,000 Wolf Man from 1941) and the film accomplished something unique for an Universal horror film — win an Academy Award, for Best Art Direction and Best Cinematography, and it was nominated in two more categories.

Phantom of the Opera, the first adaptation of the 1910 Gaston Leroux novel filmed in Technicolor, became a hit, especially in France.

Sorry to say, though, it’s not deserving of classic status.

Universal released 25 horror films from 1931’s Dracula through 1948’s Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein that are grouped together in the Classic Monsters series and I rank Phantom of the Opera only ahead of The Mummy’s Ghost, The Mummy’s Curse, and The Invisible Woman.

Lon Chaney Jr. (1906-73) felt slighted Universal did not consider him for his father’s most legendary role. Granted, he was an incredibly busy actor. Chaney Jr. had starring roles in the three films immediately surrounding Phantom of the Opera in 1942 and 1943 — his first time playing Kharis in The Mummy’s Hand, his second time as Larry Talbot / The Wolf Man in Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man, and his first and only time as Dracula in Son of Dracula. Chaney Jr. previously took on Frankenstein’s Monster in The Ghost of Frankenstein (1942) and he proved himself Universal’s most versatile monster thespian, only missing the Invisible Man and the Phantom from his credits.

Chaney Jr. especially worked as Larry Talbot / The Wolf Man, and I am imagining what he could have done in Phantom of the Opera.

Rains killed it as Dr. Jack Griffin in the 1933 James Whale classic The Invisible Man. In Phantom of the Opera, not so much, because he’s just not scary, even without his ridiculous mask when his mutilated face is revealed in the laughable grand finale. He’s not the film’s main problem, though, believe it or not.

I mean, Rains plays the freaking title character in Phantom of the Opera and he’s third-billed, for crying out loud, behind our singing leads Nelson Eddy and Susanna Foster. This never happened to Lon Chaney, who’s billed above both Mary Philbin and Norman Kerry. Rains’ Phantom becomes less of a factor and that just about sums up the failure of this particular Phantom of the Opera — too heavy on the opera and too light on the phantom.