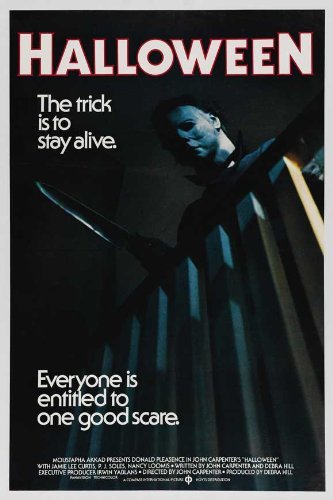

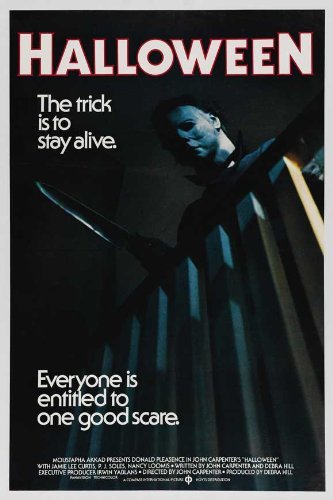

HALLOWEEN (1978) Four stars

There’s one particularly cherished moment from all the years watching HALLOWEEN.

Every time I have showed the film to friends and family, there’s one scene I patiently wait for with devilish anticipation.

I make internal bets with myself that it will work on everybody who’s seeing the movie for the first time, and it will even still work on those return viewers.

It’s a jump scare, one of the best ever filmed.

Every time, I would be taciturn leading up to this scene, not wanting to give a single thing away to my friends and family.

I wanted to see them jump, and I wanted to hear them scream.

It worked every single time.

It’s the scene where Dr. Loomis (Donald Pleasence) and Sheriff Brackett (Charles Cyphers) are discussing matters inside the old Myers house.

I won’t go any further than that.

Like the slasher films that followed, including its own many sequels, HALLOWEEN is a fun one to watch especially with several peers, but for slightly different reasons than the many, many, many followers and imitators.

First and foremost, director John Carpenter (in the words of Alfred Hitchcock) played the audience like a piano in HALLOWEEN. He’s the maestro and we love the music he’s playing, literally. The main theme in HALLOWEEN just stays with the viewer and in fact right now writing this review, I have that song playing over scenes from the first movie playing inside my head. Like other classics PSYCHO and JAWS, the music in HALLOWEEN added immeasurably to the film’s success.

Reportedly, Carpenter composed the theme in one hour, according to an interview he did for Consequence of Sound.

Carpenter discusses the movie and its music at some length on his official site: “HALLOWEEN was written in approximately 10 days by Debra Hill and myself. It was based on an idea by Irwin Yablans about a killer who stalks baby-sitters, tentatively titled ‘The Baby-sitter Murders’ until Yablans suggested that the story could take place on October 31st and HALLOWEEN might not be such a bad title for an exploitation-horror movie.

“I shot HALLOWEEN in the spring of 1978. It was my third feature and my first out-and-out horror film. I had three weeks of pre-production planning, twenty days of principle photography, and then Tommy Lee Wallace spent the rest of the spring and summer cutting the picture, assisted by Charles Bornstein and myself. I screened the final cut minus sound effects and music, for a young executive from 20th Century-Fox (I was interviewing for another possible directing job). She wasn’t scared at all. I then became determined to ‘save it with the music.’

“I had composed and performed the musical scores for my first two features, DARK STAR and ASSAULT ON PRECINCT 13, as well as many student films. I was the fastest and cheapest I could get. My major influences as a composer were Bernard Herrmann and Ennio Morricone (who I had the opportunity to work with on THE THING). Hermann’s ability to create an imposing, powerful score with limited orchestra means, using the basic sound of a particular instrument, high strings or low bass, was impressive. His score for PSYCHO, the film that inspired HALLOWEEN, was primarily all string instruments.

“With Herrmann and Morricone in mind, the scoring for HALLOWEEN began in late June at Sound Arts Studios, then a small brick building in an alley in central Los Angeles. Dan Wyman was my creative consultant. I had worked with him in 1976 on the music for ASSAULT. He programmed the synthesizers, oversaw the recording of my frequently imperfect performances, and often joined me to perform a difficult line or speed-up the seemingly never ending process of overdubbing one instrument at a time. I have to credit Dan as HALLOWEEN’s musical co-producer. His fine taste and musicianship polished up the edges of an already minimalistic, rhythm-inspired score.

“We were working in what I call the ‘double-blind’ mode in 1978, which simply means that the music was composed and performed in the studio, on the spot, without reference or synchronization to the actual picture. recently, my association with Alan Howarth has led me to a synchronized video-tape system, a sort of ‘play it to the TV’ approach. Halloween’s main title theme was the first to go down on tape. The rhythm was inspired by an exercise my father taught me on the bongos in 1961, the beating out of 5-4 time. The themes associated with Laurie (Jamie Lee Curtis) and Dr. Loomis (Donald Pleasence) now seem to be the most Herrmannesque. Finally came the stingers. Emphasizing the visual surprise, they are otherwise known as ‘the cattle prod’: short, percussive sounds placed at opportune moments to startle the audience. I’m now ashamed to admit that I recorded quite so many stingers for this one picture.

“The scoring sessions took two weeks because that’s all the budget would allow. HALLOWEEN was dubbed in late July and I finally saw the picture with an audience in the fall. My plan to ‘save it with the music’ seemed to work. About six months later I ran into the same young executive who had been with 20th Century-Fox (she was now with MGM). Now she too loved the movie and all I had done was add music. But she really was quite justified in her initial reaction.

“There is a point in making a movie when you experience the final result. For me, it’s always when I see an interlock screening of the picture with the music. All of a sudden a new voice is added to the raw, naked-without-effects-or-music footage. The movie takes on it’s final style, and it is on this that the emotional total should be judged. Someone once told me that music, or the lack of it, can make you see better. I believe it.”

HALLOWEEN, unlike its sequels and imitators, works from a minimalist base, with much fewer characters than the run-of-the-mill body count thriller for one prominent example of minimalism. HALLOWEEN gives us time with the characters, especially the three girls Laurie (Curtis), Annie (Nancy Loomis), and Lynda (P.J. Soles) and Dr. Loomis (Pleasence), and this is definitely to the film’s benefit. These characters take on a greater resonance than, for example, the gallery of grotesqueries in FRIDAY THE 13TH: A NEW BEGINNING, who only have a couple minutes of (largely) unpleasant behavior before their gruesome death scenes.

Carpenter and Hill found gold in Curtis: not only the daughter of Janet Leigh (PSYCHO) and Tony Curtis, but a great rooting interest who can be intelligent and resourceful and strong enough that we forgive her for the other moments that are standard in horror films, like (for just one example) her difficulty finding the keys with a madman bearing down on her. She’s pretty, as well, without it being overwhelming.

Annie and especially Lynda are pioneers of the Valley Girl speak, totally, and that might be one of the great sources of annoyance for anybody watching HALLOWEEN. Soles, though, is one of the more likable young actresses from that era, seen to even more effect in ROCK ‘N’ ROLL HIGH SCHOOL and STRIPES.

Likability is a key in the success of both HALLOWEEN and the first NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET.

Dr. Loomis is the character lacking in any of the FRIDAY THE 13TH movies, for example. He’s just brilliant, brought to the life by the indelible screen presence of the late Pleasence (1919-95). His character commands our attention every time he steps onscreen and definitely every time he delivers that dialogue he keeps that attention, especially about Michael Myers and “pure evil.”

“I met him 15 years ago,” Dr. Loomis said. “I was told there was nothing left: no reason, no conscience, no understanding in even the most rudimentary sense of life or death, of good or evil, right or wrong. I met this … 6-year-old child with this blank, pale, emotionless face, and … the blackest eyes – the Devil’s eyes. I spent eight years trying to reach him, and then another seven trying to keep him locked up, because I realized that what was living behind that boy’s eyes was purely and simply … evil.”

` That’s one of the best monologues in any horror film (or any film period).

Monologues like that can sometimes bring the attached film to a halt, because we don’t want to hear this psychological jive talk recited by some hack actor at just that very moment. Please, shut the fuck up (Donnie).

For example, Simon Oakland’s jive talk late in PSYCHO drags us down a bit.

Honestly, though, I could have listened to Dr. Loomis talk all day.

Pleasence sells this dialogue with the conviction of his craft and I don’t know, I’ve always got the feeling that maybe Dr. Loomis is maybe just maybe a bit mad himself all these years working around Michael Myers.

You see this Dr. Loomis coming, and you just might head to the next city or county or perhaps country, because you know he’s trouble.

In horror films, often times authority figures do not believe the stories of teenage protagonists until it’s too late, but HALLOWEEN applies the slight twist to the formula by having authority figures question the story of another authority figure.

I love the way Carpenter and his team utilize Michael Myers in HALLOWEEN: he’s driving or standing around in the background of many early shots and combined with Dr. Loomis’ dramatic playing up of Myers in dialogue, he takes on mythic proportions. Paraphrasing from Dr. Loomis, this isn’t a man. He’s a shape, and a killing force. But we also get the sense that he’s childlike and in one of the great moments for any screen killer, Myers stands and admires his own craftmanship after one kill.

He’s far more interesting with far less back story, as the sequels beginning with HALLOWEEN II irrefutably proved.

Let’s see here, we have two great protagonists, one great killer (and one great weapon), and great music.

Seems like this is the beginning of a great horror movie.