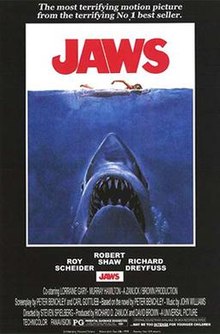

JAWS (1975) Three-and-a-half stars

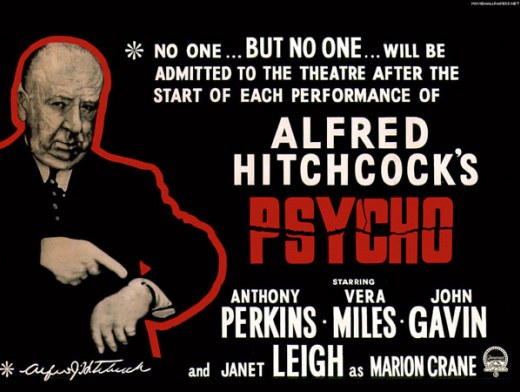

Steven Spielberg’s JAWS wanted to do for sharks what Alfred Hitchcock’s PSYCHO did for showers 15 years earlier.

Like PSYCHO, JAWS became a game-changing motion picture and it’s been analyzed, overanalyzed, parodied, and satirized, and it spawned many clones and rip-offs with just about every animal turned into a relentless killer.

It’s known as the first summer blockbuster film (released on June 20, 1975), I mean it even says so in the Guinness Book of World Records, “Not only did people queue up around the block to see the movie, it became the first film to earn $100 million at the box office.”

Before 1975, summers were traditionally reserved for dumping insignificant fluff.

Based on Peter Benchley’s best-selling novel, JAWS tells a pulp story: a great white shark terrorizes Amity Island, a summer resort community, and transplanted city policeman Sheriff Brody (Roy Scheider) wants to close off the beaches but he runs into much resistance from Mayor Larry Vaughn (Murray Hamilton), who of course fears the loss of tourist revenue more than he does a great white shark. Eventually, though, Brody, along with preppy Ichthyologist Matt Hooper (Richard Dreyfuss) and grizzled old man of the sea Quint (Robert Shaw), attempts to hunt down and kill the great white aboard Quint’s ship, the Orca.

The film and the novel are different in several fundamental ways: Hooper and Brody’s wife do not have an affair in the film; Mayor Vaughn’s squeezed by the mafia in the novel and not simply local business interests; newspaper man Harry Meadows plays a bigger role in the novel; Quint’s made a survivor of the World War II USS Indianapolis; Hooper escapes death in the film; Quint dies by drowning in the novel; in the film, Brody kills the shark by shooting a compressed air tank inside the creature’s jaws, of course.

Spielberg said that he rooted for the shark the first time he read Benchley’s novel because he found the human characters unlikeable.

Normally, books are credited for having stronger characterizations than their screen adaptations.

That’s not the case with JAWS.

In fact, none of the subsequent JAWS films could match the characterizations of Brody, Hooper, and Quint and performances by Scheider, Dreyfuss, and Shaw. We have three indelible characters who stay within our hearts and minds just as much as the image of the great white shark.

Scheider and Dreyfuss appeared to have great chemistry together, just like there seemed to be real tension between Dreyfuss and Shaw.

Universal had Scheider bent over a barrel after he dropped out two weeks before filming started on THE DEER HUNTER, due to “creative differences,” and so they forced Scheider into starring in JAWS 2. Scheider’s performance in JAWS 2 suggests a very, very unhappy person and his conflicts with director Jeannot Szwarc must have only contributed to Scheider’s apparent misery.

Dreyfuss passed on JAWS 2 because Spielberg did not direct it; they made CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND together instead. Of course, there were obvious difficulties in Quint returning for JAWS 2.

JAWS 2 gives us a bunch of teeny boppers and repeats the basic plot of the first movie, JAWS 3-D sinks even more into a morass of mediocrity (how bad must you be to be disowned by the next JAWS film), and JAWS THE REVENGE, well, it gives us the first shark movie designed for geriatric consumption. To be honest, JAWS THE REVENGE defies the suspension of disbelief beyond belief and becomes one of the worst bad movies ever made.

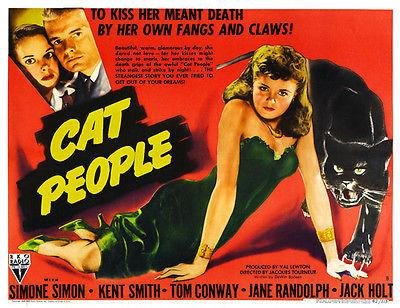

Necessity became the mother of invention for JAWS, because of the numerous technical difficulties with the mechanical shark that became known as Bruce, named after Spielberg’s lawyer, or alternately “the great white turd.” Spielberg wanted to show the shark a lot sooner, but instead the film took on more Val Lewton proportions than the average horror movie. JAWS relies heavily on John Williams’ famous musical score to substitute for the shark.

The JAWS sequels utilized the mechanical shark far more often and much earlier on, honestly to their detriment. Less is more and more is less.

I always love it when horror movies take on more than just being a horror movie. At times, especially when our three protagonists are stuck on that damn boat together, JAWS becomes grand adventure and an unexpected comedy.