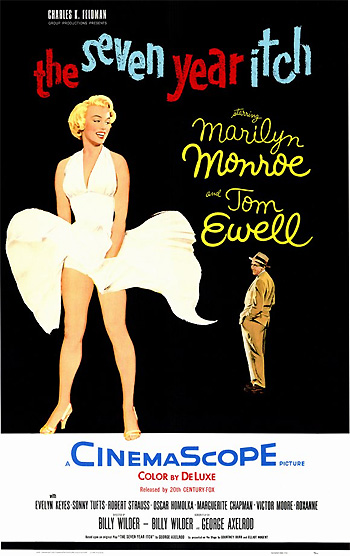

NEVER FELT MORE LIKE SINGING THE QUARANTINE BLUES: THE SEVEN YEAR ITCH, MARTY, ROMAN HOLIDAY, STALAG 17

I have become a huge Billy Wilder (1906-2002) fan after watching the great films Double Indemnity, The Lost Weekend, Sunset Boulevard, Ace in the Hole, Some Like It Hot, The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, and Avanti. Having made it about halfway through his 26 directorial credits, I have found my least favorite Wilder film so far, the 1955 comedy The Seven Year Itch.

The Seven Year Itch bombs for two main reasons — it is significantly hampered by the Production Code because the movie can’t even suggest an extramarital love affair between our protagonist and the ultimate temptation next door (Marilyn Monroe) and it centers around one of the great insufferable drips in cinematic history, Richard Sherman, played by Tom Ewell (1909-94) on a single note that won him a Golden Globe for Best Performance by an Actor in a Motion Picture Comedy or Musical. Ewell also played the part in the Broadway play.

The film’s legendary scene — Monroe’s Ultimate Upskirt — even proved to be a great letdown not worth the wait and I wish they’d have stayed with Creature from the Black Lagoon instead.

There’s nothing wrong with Monroe, of course, and she’s great in the ‘Chopsticks’ scene, but it’s that darn drip played by Ewell who ruined The Seven Year Itch for yours truly. I traveled beyond tired of his overactive imagination by about his fourth or fifth daydream, which I calculate to be about 15 minutes into a 105-minute motion picture, and having Ewell talk to himself in scene-after-scene also miserably backfired. Richard Sherman called to mind the daydreaming drip played by Gael Garcia Bernal in The Science of Sleep (2006), although Ewell did not sport a ridiculous hat.

I felt the seven year itch for another motion picture real early during The Seven Year Itch and only dearest Marilyn had me stick it out until the bitter end. It’s still no Some Like It Hot.

— What kind of world did people live in when the 29-year-old high school chemistry teacher Clara Snyder was considered a dog?

That’s the main question raised by the 1955 Best Picture winner, Marty, directed by Delbert Mann (1920-2007) in his feature debut, written by Paddy Chayefsky (1923-81) whose later credits include Network and Altered States, and starring Ernest Borghine (1917-2012) in the title role that won Borgnine the Academy Award for Best Actor over James Cagney in Love Me or Leave Me, James Dean in East of Eden, Frank Sinatra in The Man with the Golden Arm, and Spencer Tracy in Bad Day at Black Rock. Mann also won Best Director.

I asked that opening question because Gene Kelly’s then wife Betsy Blair (1923-2009) played Clara. She’s not Marilyn Monroe or Jayne Mansfield, of course, or Elizabeth Taylor or Audrey Hepburn, granted, but she’s definitely not a dog in any world. I mean, I question the eyesight and the sanity of characters like Marty’s harried mother Teresa (Esther Minciotti) and Marty’s jilted best friend Angie (Joe Mantell) when they separately confront homely 34-year-old butcher Marty late in the picture about Clara and her questionable looks. Mother Teresa goes as far to accuse Clara of being at least 10-15 years older than 29, while Angie sounds the canine dialogue until he sure does come across like a smug little prick. Marty should have belted his best friend right smack dab in the kisser, just once.

Marty devotes at least 30 minutes easy to Marty and Clara on their first date and they’re mostly just talking. Marty does the majority of the talking and Clara has this real fetching way of listening to him that makes her incredibly attractive. He cannot believe that he’s become such a blabber mouth with Clara. He’s never acted this way before. He talks about his father’s death just a month after he graduated from high school nearly 17 years ago and he considers her opinion about his notion to buy out his boss and start a community grocery store that can go head-to-head against big chain grocery stores. Marty takes Clara to his house and they are home alone for about 10 minutes. They finally kiss for the first time, right before Teresa comes home and conducts a very awkward first conversation with Clara. Marty and Clara obviously like each other, and the movie ends on Marty finally calling up Clara late in the day after their first date.

I doubt that Borgnine has ever been more likable over his lengthy screen career and the relationship between Marty and Clara undoubtedly influenced Rocky Balboa (Sylvester Stallone) and Adrian (Talia Shire) in the first two Rocky movies, especially their first date and first kiss in Rocky. I like Marty for some of the same reasons I like Rocky and Rocky II.

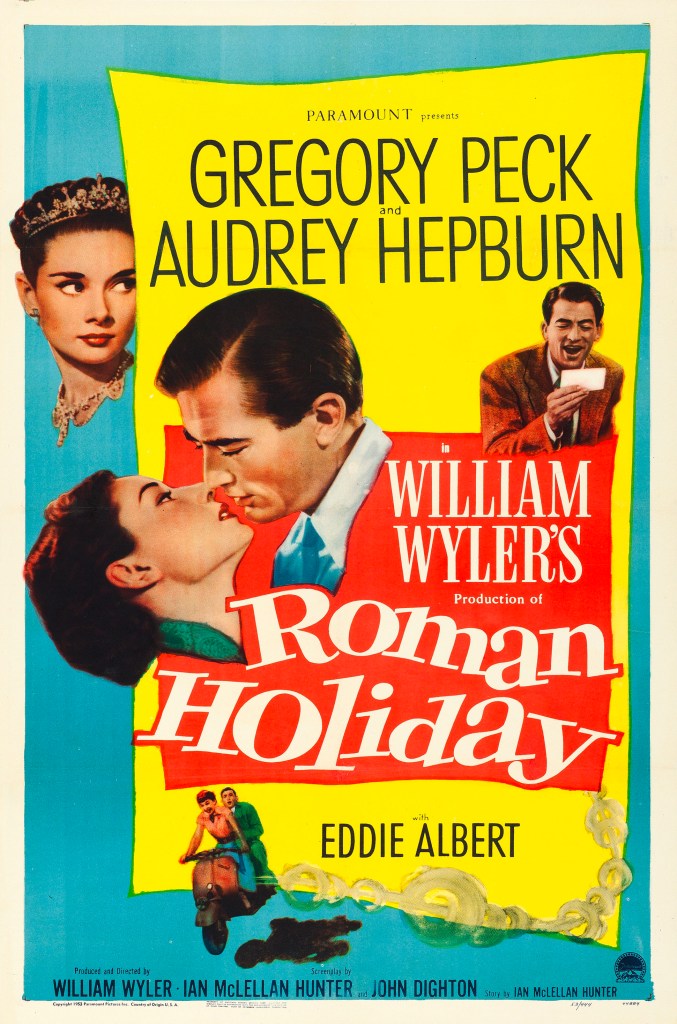

— Audrey Hepburn dominates Roman Holiday in such a way that it’s one of the performances we can point to when somebody asks for the definition of a movie star. Hepburn absolutely shimmers and sparkles throughout Roman Holiday.

Hepburn stars as Princess Ann, a traveling dignitary on a grueling schedule who just wants to have fun in historic and scenic but wild Rome. She sneaks away from her embassy, but the sedative a doctor gave her kicks in all delayed like and she begins to late night pass out on a park bench. That’s where expatriate American newspaper reporter Joe Bradley (Gregory Peck) comes in, who discovers this poor young thing that he believes got inebriated real good and therefore he eventually lets her crash that night at his apartment. One darn thing leads to another the next day: Joe discovers her true identity, decides that he will do an exclusive story and interview with Ann and he rounds up his photographer friend (Eddie Albert), and they spend one tremendous day together. Let’s see, Ann gets a haircut, she drives Joe around for a spell on a Vespa scooter, and our princess finds the opportunity to participate in a fracas with government agents called on by her embassy to grab her. Well, naturally, Ann and Joe also find time for a little suck face and other tender, bittersweet moments.

Hepburn (1929-93) turned 24 years old just a few months before Roman Holiday premiered and it marked her first motion picture starring role. She had appeared in a small role in The Lavender Hill Mob, the British picture that won the Academy Award in 1952 for Best Original Screenplay, and a few other pictures without making any significant mark. Hepburn’s breakthrough started as the title character in the Broadway play Gigi in the year or two before Roman Holiday.

Winning the Academy Award for Best Actress for Roman Holiday legitimized Hepburn’s ascent to motion picture stardom; she beat out Leslie Caron from Lili, Ava Gardner from Mogambo, Deborah Kerr from From Here to Eternity, and Maggie McNamara from The Moon Is Blue for the prize. Hepburn followed Roman Holiday with Sabrina, Love in the Afternoon, Funny Face, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, Charade, and My Fair Lady in the first decade after her first huge success and became one of the most beloved movie stars ever.

In his review of Roman Holiday, San Francisco Examiner film critic Jeffrey M. Anderson argued that Roman Holiday would have been even better had somebody with great style like Howard Hawks or Billy Wilder directed it rather than plain old staid conservative actors’ director William Wyler. Wilder directed Hepburn in Sabrina and Love in the Afternoon, and are they any better than Roman Holiday? Anderson himself gives Roman Holiday three-and-a-half and both Sabrina and Love in the Afternoon three stars. Unfortunately, I’ve not yet seen either Sabrina or Love in the Afternoon.

I’ve been on a bit of a Wyler kick lately — watching Dodsworth, Jezebel, Wuthering Heights, and Roman Holiday all for the first time — and I gained a tremendous amount of respect for the man after seeing the Netflix series Five Came Back about directors Wyler, Frank Capra, John Ford, John Huston, and George Stevens and their experiences making combat and propaganda films during World War II, and how it affected each director for the rest of their lives. Wyler lost hearing in one ear from a bombing mission over Italy; he regained hearing in that ear after the war with the help of a hearing aid. One of Wyler’s cameramen, Harold J. Tannenbaum (1896-1943), perished filming Memphis Belle; from the American Air Museum, “Shot down 16 April 1943 in B-24 41-23983. Some crew members had bailed out when the plane exploded blowing some crew clear. Tannenbaum was a passenger as a photographer from the 8AF Combat Film Unit. Losses report he bailed out but slipped out of his parachute. KIA. He was William Wyler’s first sound man on the Memphis Belle film project and was tasked to take pictures from the B-24 when it exploded on its return from Brest.”

— Watching Billy Wilder’s Stalag 17 for the first time, unfortunately I became distracted by thoughts of comparing and contrasting Stalag 17 star William Holden’s appearance in 1953 versus circa 1980 when he starred in the disastrous disaster film When Time Ran Out.

In particular, I flashed back on that wretched scene in When Time Ran Out between Holden and Charlton Heston approximate James Franciscus. Holden looks bloody awful and he can barely make it through a tiresome disaster movie scene — let’s leave it at Franciscus plays the resident nonbeliever in the impending doom. Not surprisingly, Holden spent six days in the hospital during production of When Time Ran Out to battle his alcoholism; director James Goldstone convinced producer Irwin Allen that Holden’s alcoholism posed a danger to everyone on the set, including Holden himself. Holden died at the age of 63 on Nov. 12, 1981 from exsanguination, or a severe loss of blood, and blunt laceration of scalp; an inebriated Holden slipped on a rug, hit a bedside table, lacerated his forehead, and bled to death in his penthouse apartment in Santa Monica.

Hogan’s Heroes lasted 168 episodes from 1965-71, and I must admit that I have never watched an episode in full. Back in the day, I watched many an old TV show in syndication, everything from I Love Lucy and The Honeymooners to Mannix and Quincy and beyond, but I turned the channel every time I crossed paths with Hogan’s Heroes. I doubt that all the brief time I watched it would possibly add up to the length of a single episode.

For the longest time, I held off watching Stalag 17 — despite the fact that it’s directed by Wilder — because it’s been said to have inspired Hogan’s Heroes. I watched both Robert Altman’s M*A*S*H and Martin Scorsese’s Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, and they inspired TV shows that were borderline inescapable for a youth growing up in the ’80s. So, why not Stalag 17?

Of course, Wilder had the audacity to make a comedy about a Nazi World War II prisoner of war camp less than a decade after the official end of the war.

Interrupting this regularly scheduled review, I announce that I am conceding this review. The writing’s on the wall, rather than on the page, because after 40 days it’s finally clear that I am not going to discuss in any significant detail Wilder’s clashes with Paramount, how Stalag 17 both established and subverted the P.O.W picture, etc. I thought about writing all that more than actually writing it, you know, and that just doesn’t work in the long run. Too bad, there’s not a way to directly transfer dreams and inspirations from the brain to the page. Then again, on deeper thought, maybe it’s good there’s not that way.

Looking back at the permanent record, I watched Roman Holiday, Stalag 17, and The Seven Year Itch on Nov. 17 and Marty on Nov. 18, all four near the end of a 18-day quarantine period, so it’s not exactly been 40 days as I write this concession speech. It just feels like 40 days or maybe 400 or maybe even 400 thousand, because in this crazy year called 2020 perspective’s been permutated, warped, contaminated, mangled, displaced, isolated, and disputed. Here’s to a major comeback for a bruised and battered human race in 2021.

The Seven Year Itch **; Marty ***1/2; Roman Holiday ***1/2; Stalag 17 ***1/2