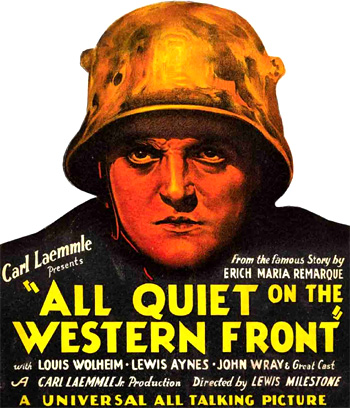

ALL QUIET ON THE WESTERN FRONT (1930) Four stars

Working on a master’s degree in history (world history emphasis), the last three credit hours I needed were from an internship.

In the summer of 2005, I worked a three-week, 120-hour internship at the National Archives (no, I did not see Benjamin Gates or Nicolas Cage playing another character, for that matter) on Bannister Road, Kansas City. I worked a week on a file project, utilized a spatula to remove “sensitive” staples from at least 100-year-old Fort Leavenworth prisoner files (another week), spent a day looking up family history, and visited what became the National WWI Museum and Memorial. In the past, before September 11, 2001, of course, interns were allowed to keep both their federal employee badges (needed to enter the facility) and their spatula. I settled for a picture of the badge.

At that point in time in the WWI museum, they only had the gift shop completed and open to the public, so I bought a Buffalo Soldier T-shirt (absolutely loved that design) and German author Erich Maria Remarque’s remarkable book “All Quiet on the Western Front,” a book originally released in 1929 and made into an Academy Award for Best Picture winner in 1930.

I wanted to go back to the Archives as full-time employee, but alas, it did not come to be after multiple tries. Finally, in 2008, after three years of frustration and substitute teaching (just another phrase that means “frustration”), I returned to Pittsburg State and embarked on a new path that led to where I am today.

(Of course, when I did the internship, I enjoyed telling people, “I work for the government. … I could tell you, but I’d have to kill you.”)

I watched the movie before I read the book and both are essentials. However, I’ll just focus on the movie (directed by Lewis Milestone) within this space.

We follow a group of German young men, predominantly Paul Baumer (Lew Ayres), from when they’re idealistic prep school students who are inspired to enlist by their jingoistic teacher to their inevitable disillusionment after being hit straight in the face with the brutal realities of World War I. Death, mutilation, rations, starvation, trench warfare, on down the line, and finally Paul asks the fundamental questions of life and death and what exactly is he fighting for.

When he returns to his old classroom where his former teacher still gives the students the same old propagandistic spiel as before, Paul confronts him and the students, “We used to think you knew. The first bombardment taught us better. It’s dirty and painful to die for your country. When it comes to dying for your country, it’s better not to die at all! There are millions out there dying for their countries, and what good is it?”

The students yell and scream COWARD at Paul.

Of course, one would be easily tempted to say that it’s much easier telling an anti-war story from a German perspective, since war is more Hell for the “losing” side. Notice the difference in World War II movies from Germany and Japan versus movies from Great Britain and the United States, for example.

Francois Truffaut (1932-84), first a film critic and then a director himself whose credits include THE 400 BLOWS, JULES AND JIM, and THE WILD CHILD, reportedly told Gene Siskel in a 1973 interview, “I find that violence is very ambiguous in movies. For example, some films claim to be anti-war, but I don’t think I’ve really seen an anti-war film. Every film about war ends up being pro-war.”

Anyway, Truffaut became famous for saying “There’s no such thing as an anti-war film”; for example Roger Ebert used it when reviewing PLATOON. The actual original Truffaut anti-war film quote seems to be quite elusive.

The thinking behind the quote (whether Truffaut said it or not) is that movies glorify whatever behaviors are being shown or war movies make war seem attractive, glamorous, et cetera, basically cinematic propaganda that’s an upgrade on what Paul’s school teacher tells generations of young men in the classroom.

On that train of thought, it makes ALL QUIET ON THE WESTERN FRONT pro-war rather than anti-war, despite any noble intentions and whatever dialogue comes out of the characters’ mouths.

However, ALL QUIET ON THE WESTERN FRONT definitely had an impact on Lew Ayres, the 22-year-old actor who played Paul.

Ayres became a conscientious objector during World War II, basing it on his pacifism. Ayres said, “To me, war was the greatest sin. I couldn’t bring myself to kill other men,” and he told the draft board in Beverly Hills, “Don’t think I am trying to save my neck. I would like to be of service to my country in a constructive way and not a destructive way.”

Since Ayres did not belong to any organized religion and did not have any formal religious training, he faced long odds in being classified a CO. The draft board deliberated on Ayres’ case for months and they mistakenly classified him IV-E, meaning that he objected to all military service. Ayres preferred to be I-A-O, meaning that he could have noncombatant military service like the medical corps he most desired. The draft board assigned the IV-E Ayres to a labor camp in Wyeth, Oregon.

The public, especially the Hollywood community, hit Ayres with a major wave of backlash. Of course, this was early 1942, months after Pearl Harbor and months after the United States surrendered neutrality and joined World War II against the Axis powers (basically Germany, Italy, and Japan). It looked extremely bad for a Hollywood actor to be a conscientious objector.

A soldier, though, wrote a letter of support to Time, “Lew Ayres, instead of being detrimental to our public good, is indicative of what the American people wrote into their Bill of Rights and what we fight our wars about, the right to freedom in a democracy.”

Over a month later, the draft board reclassified Ayres I-A-O.

Ayres received the assignment to the medical corps that he desired. He served 3 1/2 years in the medical corps and earned three battle stars.

In a story called “The ‘Good’ Conscientious Objector Lew Ayres,” writer Joseph Connor quoted Ayres on his experiences, “I had imagined that war was a horrible thing. But it actually surpassed anything I’d dreamed of. It’s bad enough in the field, where soldiers expect cruelty and death; but in cities, among helpless civilians, the picture is far worse.”

Ayres said that he found it the most difficult to attend to children with bullet holes in them.